The Slip Coachby Adrian Vaughan(This article was first published by Adrian Vaughan on his website, 14 November 2011. Photos are by Adrian Vaughan unless otherwise indicated.) |

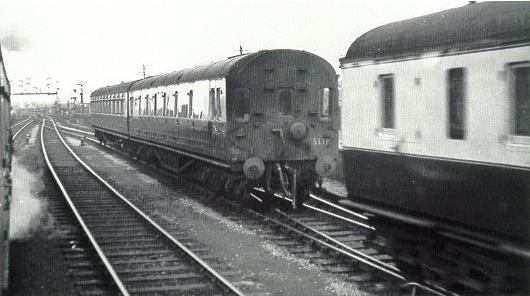

A Collett double-ended slip coach, diagram F23, coupled to what looks like a Toplight composite, being slipped on entry to Reading's up main platform.

(photo from the webmaster's collection) |

The 'slip coach' is an idea taken from the days when railways were being constructed. Before any train ran. The wagons carrying spoil to the head of an embankment, to drop the load over the edge, had a 'slipping lever' to uncouple the horse from the wagon. The horse stepped sideways and the wagon could be pushed the last few feet and tipped. When trains began running, those being 'gung-ho' days when risk assessments were not much thought about, the fireman – on some railways – would climb over the coals and when the driver eased off speed, the coupling went slack and the fireman could then lift the coupling off the hook. The engine then accelerated and the pointsman switched the track into the depot and turned the points back again to send the train into the terminus station. This practice caused a fatal crash at Hull in about 1840 but the slip coach idea was continued. The GWR is most famous for using them but most major companies had slip coaches, some more than others. It was a very dangerous practice when the only brake was the guard's handbrake and safety depended on the main train not slowing down after the slip had been made. With the introduction of a powerful vacuum or air brake it was less dangerous but still dodgy – in my opinion. The GWR had a printed instruction to level crossing keepers in its 'General Appendix to the Rule Book' ordering them to remember which train had a slip coach and not to open the level crossing gate after such train had passed until the slip coach had also passed. And thereby hangs a tale, I think. In spite of the obvious danger of having a loose coach whizzing along at a respectful distance behind the main train I have only heard of one slip coach collision. That was at Woodford Halse in 1935. The coach was slipped on a foggy day – and maybe the guard ought not to have slipped – but he did – and then the main train slowed down, he caught up with it and, because of the reduced visibility by the time he saw it he could not stop in time.

Before 1914 the GWR had 72 coaches slipped every weekday. During the war slip coaches were discontinued and after the war nothing like so many were put on. The classic slip coach train was the GWR's 'Cornish Riviera Limited' which left Paddington at 10.30 a.m daily with three slip coaches – one for Weymouth, slipped near Westbury, one for Minehead, slipped at Taunton and one for all stations Exeter to Newton Abbot, slipped at Exeter. As the spring came and Easter, as the holiday season got going, the slip coach would have an ordinary coach coupled behind it and as high season developed the slip coach was abandoned for a 'Relief' train of maybe 6 coaches for Weymouth or Minehead.

Each slip coach could have up to four 8-wheeled coaches behind it – or six 4 or 6-wheeled coaches – but that many was very unusual.In the 1910 timetable there were a couple of trains booked to have three behind but usually it was only one. The more coaches there were behind the slip the greater skill was required from the slip guard because of the technicalities of the vacuum brake system – explained in the next paragraph. If running with three or four behind the slip then the slip coach might be a 'single ended slip' – i.e. the slip coupling was at one end only and there was a corridor connection between the other end of the slip and the four ordinary coaches. But this was not obligatory.

The slip coach coupling had a drawhook that was hinged at the base and when the pointed tip of the hook when lifted up into the normal position it had an iron casting an inch above it. Into that space fitted a wedge, filling the gap and holding the hook in place. In the slip guard's compartment there was a lever which stood upright between two guide bars. When pulled backwards it pulled the wedge back allowing the hinged hook to drop. Pulling the lever back also turned a rotary valve which then admitted air into the vacuum brake cylinders of the coach and the coach or coaches behind. So the slip coach was at once braked and dropped back from the main train. The guard then pushed the lever fully forwards. This rotated the said valve and allowed the air pressure which was then in the train pipe and brake cylinder(s) to depart into a large vacuum chamber under the slip carriage. A vacuum chamber is a steel container where the air pressure has been considerably reduced below that of the outside atmosphere. On the GWR the vacuum was equal to 25" of mercury and so while outside the atmospheric pressure would be 14.7 lbs per square inch inside the vacuum chamber the pressure was 4 or 4½ lbs psi.

When the valve allowed the air in the brakes to pass into the vacuum chambers, the pressure on the brake cylinders was removed and the brakes were released – but the pressure in the vacuum chamber had been increased. If there were four coaches ration of air to enter the chamber the pressure would be raised four times more than if there was only one slip coach discharging air. If the guard was unskilful with four coaches behind his slip he could, perhaps, fill the vacuum chambers and then when he next tried to discharge the air there would be nowhere for it to go. But let us assume that all is going well, the brakes were released and the coach free-wheeled happily along. All that was then required was for the guard to pull the lever back and apply the brakes as he coasted into the station. Therefore the important thing for the slip guard to do was to slip his coach at the right distance from where he had to stop having regard for the gradient and the speed of the train. There is no doubt it was skilful and would have given great satisfaction to the slip guard when he could perform the feat perfectly. |

The home signals of Reading Main Line West signal box for an Up Train off the Berks & Hants Line. The four top arms route to: Up Relief Line; No.7 Bay Line; Up Main Line; Bay Lines (Platforms 1–3). The slipping distant for the platform line is cleared. The left-hand arm is for use if the train is going to slip the coach on the Up Relief Line platform. There is a 'Calling-on' arm below No.7 Bay home signal and there is a permanent reminder to drivers that there is a speed limit of 10mph into the Bay.

Reading West Main's Up Relief Line Home signals. The arms are, left to right: Up Relief Line to Up Goods; Up Relief; Relief to Main. The slipping distant is on the upright post below. |

In the summer it was often the case that there were more passengers than could be accomodated in two or three carriages behind the slip and so the noble GWR put on an extra train – maybe 6 coaches (try doing that on our 'world-class' railway) in place of the Weymouth slip and the Minehead. These would then run as a 'part' of the main train – i.e. '10.30 Paddingon, First Part will depart Paddington 10.27 a.m' or 'at 10.33 a.m'. It was normal at peak times of summer travel to have the main train and three – or more – 'parts' – one for Weymouth, one for Minehead, one for Ilfracombe. These 'parts' had their timings in the Working time table 'Suspended' and then when the train was to run it was shewn on the working notice for that week '10.25 a.m Paddington WILL RUN' written like that. It was brilliant railway. In spite of all the so-called 'inefficiencies' of the equipment they really tried for the passengers.

I rode up from Plymouth several times a year for 2½ years in the slip coach of the 8.30 Plymouth, slipped at Reading about 1 p.m. In all cases where there was a slip coach shackle was placed over the ordinary drawhook of the last coach of the main train and the vacuum pipes were connected without the self-sealing adaptors. The coupling altered at the last stopping place. The 8.30 Plymouth 'adusted the slip couplings' at Westbury. This meant putting the shackle of the last coach of the main train over the drawhook of the sli coach and self-sealing ends fitted to both vacuum pipes – on the slip and on the main train. The guard of the main train walked through the main train nearing Westbury and inquired over every passenger if they were travelling to Reading and if so to get out at Westbury and walk back to the slip coach. Then he came to the slip coach and asked if there was anyone on board for Paddington – in which case to get out and go forward into the main train. I have spoken to a driver who used to work up from Plymouth in the 1950s and he said that if they had to slip at Reading he would be careful – signals permitting – not to use his brakes at all to come around the bend at Reading, off the Berks & Hants Line and into the Up Platform Loop at Reading at 20mph. He had the brakes fully off and the vacuum chambers above each brake piston and underneath the slip coach fully exhausted and did not want to interfere with that. He said he would shut off steam at the right place and free-wheel, losing speed so that he entered the platform loop without using brakes. As he came under the great signal gantry at Reading he kept his eye on the vacuum gauge in his cab because that would tell him when the slip guard had detached the coach. When the slip was made, the vacuum pipes parted between the main train and the slip coach and the Train Pipe needle of the gauge would dip briefly as air ran in as the pipes came apart and before the automatic sealing valves worked. Once he saw the needle dip he would put on steam. Everything on the mechanical railway was down to the skill of the men doing the work.

Up until 1953 I regularly saw the 8.30 Plymouth and the 8.20 Weston-super-Mare slipping at Reading at 20mph. The whole train would be sent through the Up Main Platform (No.5) Loop and at that speed the guard did not pull his lever until he was just on the platform end. We boys used to crowd to that end to catch a glimpse of him doing this. Moving out to between Didcot and Swindon I did on one or two occasions stand on Foxhall bridge and see the 8.30 Weston go through at 70 and then the slip coach appear after a minute or so all by itself, rolling along! An amazing sight.

One last point. Not only did the slip coach break the solemn rule that there must never be two trains in one block section but it also broke the rule that there should only be one tail lamp on a train – on the last vehicle. A train carrying a slip had the 'Main Train' tail lamps on the last coach of the main train – two red lights one above the other – made as a single unit for ease of handling, and the slip coach had 'First Slip' lamp, a red and a white side by side and also built as a single unit. If there were two slips the last slip carried this lamp – because he was first to go – and the inner slip carried a red and a white one above the other but if there were three slips then the last to go – the third slip – carried a triangular formation of tail lamps, a white and a red side by side with another red above those two. |

The Down Distant signal for Bicester with the slip guard's repeating distant, worked from the same wire that works the main arm.

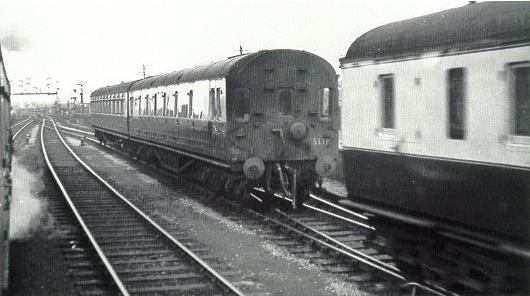

A double-ended Collett slip coach, diagram F24, at the rear of an up train on the approaches to Reading.

(photo from the webmaster's collection)

|

'By slip coach to Bicester', an extract from the Railway Roundabout TV series featuring the last ever slip coach operation in the UK on 9 September 1960. The slip coach, number 7374, is one of the three Hawksworth slip coach conversions, and remained in BR chocolate and cream at that time.

Further reading: Slip Coaches

|