|

Conical 17-gallon milk churns

by Russ Elliott

|

A busy scene at Paddington. A number of churns on the lorry are inverted, which means these are empties being loaded onto returning down trains. The churns are being loaded into a diagram O4 'low' Siphon, and the vehicle behind looks to be a diagram Y3 Fruit Van, which were seen on milk traffic duties when not being used for seasonal fruit traffic.

Photo by permission of and copyright Pat Cryer.The unedited version is on display at the Swindon Steam Museum. |

|

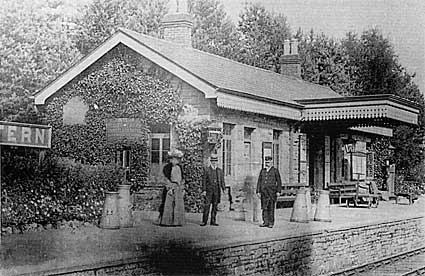

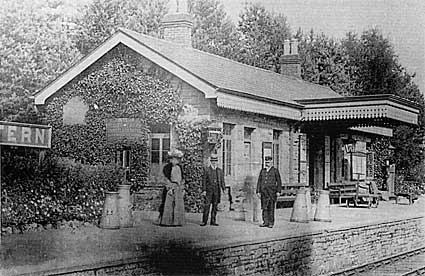

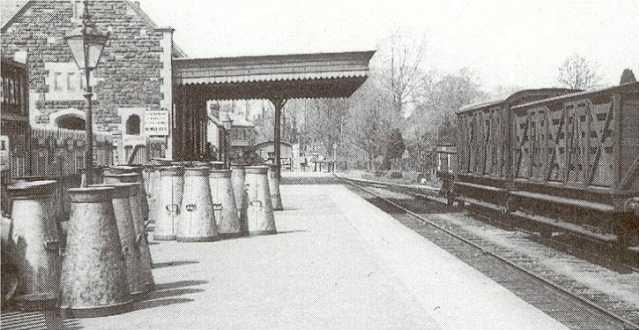

17-gallon churns awaiting collection at Tintern, c 1900, the two churns on the left showing the difference in height between the earlier shorter type and the later taller type

picture: Lens of Sutton |

|

Churns aplenty at Paddington being loaded into a down express, 3 July 1923.

Most of these conical ones are the taller version. There are however a few smaller (probably 10-gallon) cylindrical churns. |

|

Churns on the arrivals side of Paddington opposite the as-then-numbered Platform 6, c 1910. This loading/unloading area was situated between the station and Bishops Road Station. |

|

On the platform at Malmesbury, c 1920s. The sun's angle indicates this is mid- to late afternoon. Churns were made of galvanised iron, so portrayed a dirty/mottled light grey colour after they had been in traffic for a while. Note the rim at the base of the churn and the upper conical part is a slightly darker colour compared to that of the main body. Siphon vehicles await in the loop.

Malmesbury dispatched 68040 churns in 1925. |

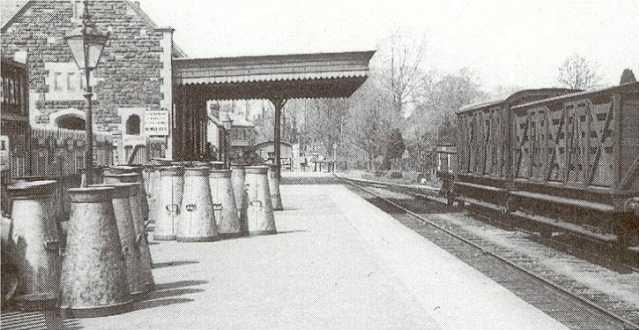

Stapleton Road, c 1912

|

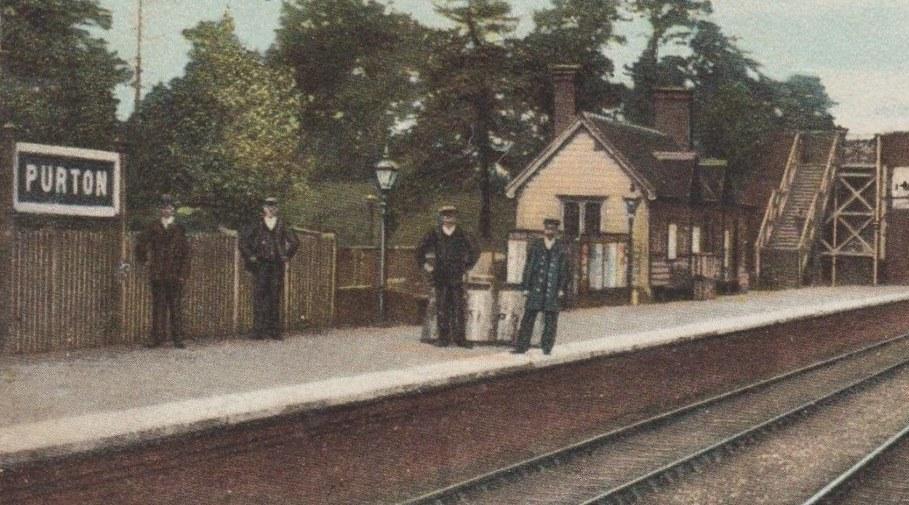

Watlington, 1919 |

|

Highbridge, 1928 |

|

Many churns carried a plate denoting the maker or owner, usually being the diary company, e.g. 'Express London Dairy Co', and sometimes it or the cap would be marked with its 'home' station. |

| Typical dimensions of two types of conical 17-gallon churn. The shorter, squatter, one is an early version, and was superseded by the more common later taller version. Handle styles varied, some pointing 'up' and some pointing 'down'. I think cap sizes varied as well. (The caps were a pressure fit.) My thanks to Dewi Jones for the prototype measurements. |

Note: The only known Swindon drawing showing the taller churn is undimensioned, but scales the height at approx 36.5". Possibly the draughtsman took the dimension to be a nominal 3'. It is likely though that minor variations of dimensions did occur between the various churn manufacturers.

|

| It is unclear why the taller version of the conical churn became the norm, but it certainly had an impact on how churns could be stacked in the 'Siphon' vehicles most commonly used for their transport on the GWR. Here's a sketch showing the different stacking heights of the two types of conical churn, but please note I'm not sure of the exact height of the churn bottom from the bottom of the lower rim, so these stacking heights are approximations. Nevertheless, the taller churn was probably the reason for the introduction of the the 'high' Siphon variants (e.g. diagrams O5 and O6). Although there might be just enough headroom inside a typical 'low' Siphon, e.g. an O4, for double-stacking of the taller churn, I think it would be a very tight fit, bearing in mind the door height clearance when loading and unloading. |

|

Packing of churns inside a 6-wheel siphon was dictated by the speed of manual loading and unloading, quite a lengthy process, and loading time would be at a premium at an intermediate stop. (Early 6-wheel Siphons had two sets of double doors per side, whilst later ones had three sets of double doors, to facilitate speedier loading.) The number of churns inside a particular vehicle would depend on the amount of milk being loaded into the vehicle at its loading station. Whilst an effort was made to ensure loaded churns would not be subject to movement when vehicles were braked, the number of churns inside a vehicle would vary – vehicles were not 're-packed' en route, which would have been too time-consuming. From the pictures in the HMRS Siphons book, it is clear that double stacking did take place, but its extent and how common this practice was, and whether this was in respect of loaded churns or empties, we do not know.

| In the hypothetical extreme loading case, a double-stack of churns within a fully loaded 6-wheel Siphon could amount to a maximum of approximately 120 churns, which would be just over 2000 gallons, representing a loading weight (inclusive of the churns themselves) of say 15 tons. With the tare weight of a typical 6-wheel Siphon being 10 tons, a fully loaded vehicle would therefore be in the region of 25 tons. The reason 6 wheels were preferred for the slatted Siphons rather than 4 was therefore not because of axleweight, but because milk trains were run at express speeds, and milk needed a smooth ride. |

|

The question of the disposition of loaded (or empty) churns within a Siphon and their double-stacking is problematic. For double-stacking to take place, I think it would be impossible to put a full first layer in and then try to put another layer on top – there just isn't the headroom to work those kinds of weights in my view, even for empty churns. Full single churns were usually manouevered by a single man by rolling on the churn bottom rim, but a straight lift onto a second layer would probably require two men, and two men working inside a Siphon would require space to move. Full or even empty churns could not be 'rim-rolled' on top of an existing first layer. Much more likely is, where the number of churns was large and extra vehicles were not available, that double-stacking would take place from the start of the loading process, i.e. filling up the ends and non-door middle spaces first. That said, a full 17-gallon churn would weigh in the order of 250 lbs, so double-stacking, where it did take place. is more likely to have been in respect of empties rather than fulls. Hence the '120 churns max' in a 6-wheel Siphon is very much a conjectural notion, and I can't imagine it would ever have been achieved (or thought necessary) in practice. Far easier, and less time-consuming, would be to start loading another vehicle, of which there were usually plenty in a typical train. Loading/unloading times would seem to have been an important factor for milk trains, especially at intermediate 'pickup/setdown' stops. A more typical and common overall situation would be of partially loaded vehicles, and that seems to be borne out by the pictures in the HMRS book.

The longer and later bogie Siphons, e.g. diagrams O11 and O12, could in theory accomodate many more churns per vehicle, but an official 1930 drawing of an insulated Siphon J specifies the loading capacity to be "100 to 116 churns".

The Highworth branch generated considerable milk traffic. This is Stratton, with a milk train hauled by a small Metro tank. The leading vehicle is a 6-wheel low Siphon, the next a 6-wheel high Siphon, and the vehicle closest to the camera is a Dean 40' PBV, possibly a diagram K4. Platform trolleys were obviously the favoured method of transfering churns to and from vehicles at this location, and there are at least eight of them in this picture. (Platform trolley numbers and ergonomics could get complicated where any empties had to be unloaded first before the new fulls could be loaded.) The direction of the train is toward Swindon, so this is an up train, and it's a reasonable assumption that these churns are full. The platform trolleys, probably pre-positioned on the plaform prior to the train's arrival, and wheeled in tight to the train doors, have 3 (maybe 4) churns each – the number of churns being loaded into each vehicle would seem to indicate that no attempt at double-stacking was made here on this particular occasion. It is likely that the train would be joined with other up milk train vehicles at Swindon for onward route to London.

In the 1920s, it is thought that over 60 express milk trains ran on the GWR every day to various towns and cities. In 1922, the GWR transported 75 million gallons of milk.

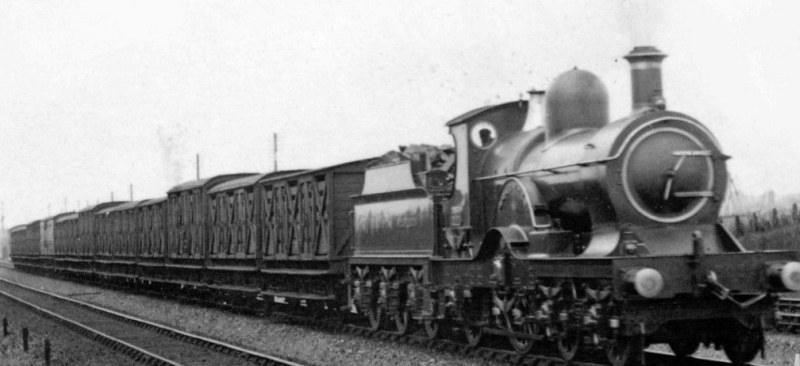

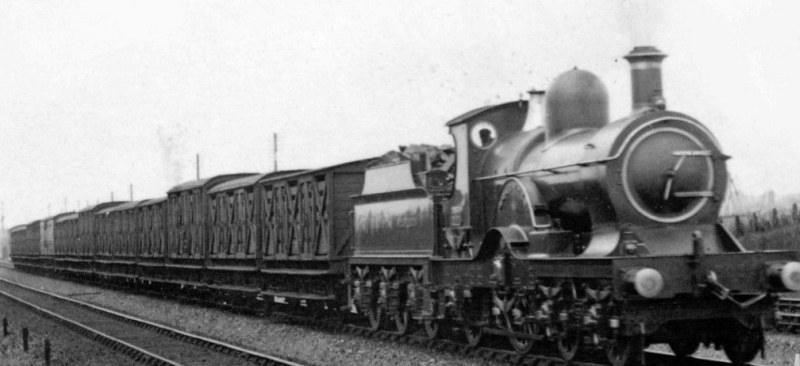

Displaced from toplink express passenger duties by newer 4-4-0s and 4-6-0s, Dean Singles found use on express milk trains in their last days. On 9 September 1908, 3034 "Behemoth" hurries an up train towards London. The loco would be withdrawn a month later.

|

At Southall, the doors of newly-outshopped Express Parcels railcar 17 struggle to cope with churn loading. |

Conical churns began to be superseded by the 10-gallon parallel-sided cylindrical type of churn introduced in the 1930s, although some cylindrical types were present before that date. David Walley has kindly provided a pic of his cylindrical churn, whose approximate dimensions are 29" height and 13" diameter.

Dana Ashdown kindly submitted the picture adjacent of 10-gallon cylindrical churn, which is of Canadian origin:

- overall height is 23"

- height to the top of the upper reinforcement ring is 16"

- diameter overall is 13¼"

- width of lower reinforcement ring is 2½"

- width of upper reinforcement ring is 2⅛"

- distance between reinforcement rings is 11½"

- diameter of lid is 11"

- depth of lid is 1½"

- width of handles is 5" (excluding mounting tabs on either side)

I have no reason to question the quoted dimensions of the above churns, but the discrepancy in height does seem strange.

| Collecting churns at a farm loading platform. Date and location unknown. |

|

Further reading:

– Great Western Siphons, J.N. Slinn & B.K. Clarke, Historical Model Railway Society;

– Milk deliveries in working class London in the early 1900s (Pat Cryer's delightful page based on Florence Cole's childhood recollections of working class life in north London in Edwardian times).

|